- Lara Fank

- Jan 23, 2025

- 14 min read

Updated: Jun 19, 2025

From The Pluriverse

Yasia Khomenko: Crafting Social Interaction to Build Resilience and Togetherness

Reinventing creative practices and creating community support through collaborative upcycling

by Lara Fank

Photos by Dmytro Prutkin

There are countless examples from around the world of crises bringing communities together, particularly when governments and big institutions fail to provide support. The war on Ukraine is no exception. OC.M speaks to Yasia Khomenko, a Ukrainian former fashion designer, turned artist based in Kyiv.

In the face of displacement, trauma from the war and also a deep frustration with the fashion industry, Yasia began to question her relationship to design and consumption. Driven by her desire to help local communities through loss and destruction, and just bring people closer together, she developed a textile practice based on community participation and interaction.

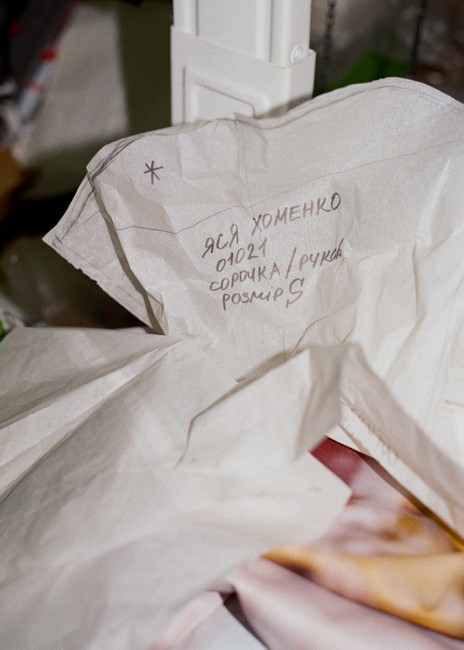

Yasia runs the ongoing project ‘The practice of social interaction’ in the form of textile upcycling workshops in which participants – which Yasia recruits through museum callouts, her network and sometimes even Tinder – are invited to bring clothing they would like to rework, to tell the stories behind each piece and and to then combine the materials into something new, utilising a unique compression technique which she initially developed for her brand. This collaborative process ends up in exhibitions, showcasing the reworked items alongside their stories. These have been exhibited in museums across Europe.

Yasia talked to OC.M’s Lara Fank about turning her back on capital-F Fashion, making the switch from commercial to community-based practice, community support in the creative scene in Kyiv in the context of the war and the importance of constantly questioning and reinventing our creative practice and ourselves.

"The most important thing that fashion and crafts practices should bring about, is that people no longer identify as consumers. That’s true sustainability".

Lara Fank: You founded your brand XOMEHKO in 2019 using a very distinct process of compression of upcycled materials. How did you first get into your upcycling practice? And what was your experience of being an upcycling designer in the capital-F Fashion world?

Yasia Khomenko: I always wanted to be an artist. But my mother encouraged me to become a fashion designer because, seeing the big luxury fashion shows, she thought there would be a lot of money to make in the fashion industry. From the outside, people see the fashion industry as super posh and luxurious, but actually, it’s a lot of hot air.

I started out my upcycling design practice, not because of sustainability, but because of my family’s excitement for second-hand clothing. Growing up in the 90s in Ukraine, the only really good clothes you could find were at flea markets. The resale of donated clothes was a big business in Ukraine and going to the big markets was part of our family routine. So, when I started to design my first collection, I couldn’t imagine using something new.

When I started out, it was really tough because “second-hand” in the fashion industry was a swear word until about 2015 when Vetements showed reworked jeans on the runway. And after that the big wave of upcycling brands arose.

I think I was always designing more for fun. It wasn’t about wearability or about business. I was making art, but in a fashion framework. And when I came to a point where I either needed to grow up to a business level or quit, I realised that I couldn't fit the business model because I don't believe in the fashion industry, and its priorities.

And finally, the main disappointment for me was when I took my brand, which was based on compressing used clothes into new pieces, to a Paris showroom. I spent a lot of money to attend the showroom and got a lot of positive feedback from buyers, but they were asking if I could scan the compressed textiles and print the texture instead to fit the market and for scalability. I understood that that’s not the way I want to go. So, I realised that I don’t want to be in that field anymore, that was my last season as a designer, and I went into the art field. That’s my story of being in fashion.

Lara: You then moved from an individualised design practice to adopting a more community focussed approach to your work. How did this shift come about and what led you to initiate your projects ‘Humanitarian Aid Project’ and ‘The practice of social interaction’?

Yasia: I think I felt this inner desire to move towards a more community-based practice because - while being a designer for my brand - I felt limited and restricted in what I designed, as compared to working collaboratively with others.

When I started working with the compression method, I tried to give space for uncertainty, to create unexpected combinations of materials. But then I looked at the combinations and thought: “Ok no, I can’t do that.” But now that I am working in collaboration with people, it's freeing to have them come up with combinations as they wish and I am learning to let go of controlling the design. Even now, I sometimes feel like I want to intervene, to make the process easier and help create a “fancier” outcome, but I always stop myself from intervening in their work.

I think the biggest change came in 2022 with the full-scale invasion [of Ukraine by Russia] and that forced my family and me to become refugees. This caused a big reorientation, transformation and deconstruction for me, first of all, as a consumer. It was the biggest change for my perception [of consumption] because I no longer felt a connection with the material world.

The ‘Humanitarian aid project’ took place in March 2022, while I was staying in Ivano-Frankivsk. I was a refugee without clothes and went to a humanitarian aid centre, as a consumer so to say. I didn’t feel like a refugee, I didn’t want to wear these donated clothes. I was waiting for the shops to open, but everything was closed because of the war, and the whole situation of panic and fear. So, I took some of the donated clothes and tried to wear them, but I realised that people only donated their last clothes, the most damaged.

I got permission from a local cultural organisation to work with clothing that was super damaged - even mouldy and unsuitable to be distributed to displaced people - to combine and rework it, which I turned into seven or eight sweatshirts. I felt this courage to work with humanitarian aid clothing to fix this experience of my life through this project.

Social relationships became the most important at the time. Being a refugee, everything you need is just social support, appreciation and help. That's why in the west part of Ukraine, Ivano-Frankivsk, where we fled to in the first months, I felt a really big connection with the local community. Connecting with community, getting involved in humanitarian aid projects and helping the army helped me to destress.

So, that's how my work became more about social interaction and sharing. I started ‘The practice of social interaction’ because I had no other way of expressing myself. I was not safe. I felt super abandoned. I didn't have my usual daily working routine. I didn't even have my equipment or my team around me. So that's why I decided that the Łódź Central Museum of Textiles [Łódź, Poland is where the project took place for the first time] is the perfect place, a former factory to start my own ‘factory’ with people who had the desire to cooperate with me.

One individual workshop can last up to three days. It’s important for me to take the time with people one-on-one. A lot of people that work nine-to-five and have a strict, dull routine crave that time and space for creativity. I really want to interact with people who are not from the creative field and don’t have any experience working with textiles.

‘The practice of social interaction’ is this idea of a new, collaborative factory, a playful way of interaction. It’s not necessarily critical, not a war against the industry, that I want to conquer or ruin. I just want to play.

"There is no chance to create these kinds of emotions while being a designer. Fashion design is the opposite, it’s about ego and posh life immitation."

Before, when I thrifted all these second-hand clothes to rework into my designs for my brand, I always wondered what the story was behind these clothes. Working with people gives me a chance to hear their stories and to become a part of it. One of the workshop participants’ clothing items belonged to their grandmother who died of cancer, and they were very close. The grandmother was an artist, and she [participant] wanted an item of hers to be a part of an art project. There are so many tremendously interesting stories behind each item.

I like how people treat this project like something sacred. To me that’s tremendously meaningful. There is no chance to create these kinds of emotions while being a designer. Fashion design is the opposite, it’s about ego and posh life immitation.

"Crafting is a universal language. [...] You find humour and common senses while crafting in common."

Lara: You no longer see yourself as a designer and you said you don’t want to be an instructor during the workshops, nor interfere with participants’ creative processes. What role do you take on during the workshops?

Yasia: Sometimes, the format is a group workshop to build community. I try to actively facilitate community and connection, especially when working with refugees. I held one workshop in the Netherlands. A lot of the Ukrainians who participated hardly spoke English. They find a common language while crafting. Crafting is a universal language.

It’s very cool because people also start to relax while crafting. You find humour and common senses while crafting in common. This is nothing new that I invented. There has always been some kind of common crafting in ancient times across different nations. But unfortunately, crafting was often very gendered – only women doing one craft and men another, or only one kind of age or social group. So, creating social communities made up of different, multinational people is a very interesting and important process.

For example, in Dresden, I was working with an Iranian woman who was between 50 and 60 years old. Her son was murdered shortly before she attended the workshop. I was super stressed because I couldn't imagine how to work, interact or communicate with her, not to retraumatise her. But she really wanted to do the workshop so we spoke through Google Translate.

During the workshops we really found a deep emotional connection. I could see she really needed that workshop. She was cut off all social life because of conservative norms that restrict women of her age to the home. The workshop was a safe place for her. She felt a deep connection: she was bringing me food, we talked about her family, and she was messaging me every day: “What can we make today?” The result of what we made was not important but the connection we made was.

I realised how many stories are still untold and how many people still need to be involved in creative projects and creative communication, to reconnect with their material wardrobe, to tell their stories, to cut up clothes that hold a triggering memory.

Maybe the project looks unnecessary or childish, but I think it is very important. And the more I go into this practice of social interaction, the more I realise how important it is to continue, not to stop it –how important it is to create new social connections, how cool it is to find new ways of allowing people to do whatever they want to.

Lara: That's beautiful! This notion of a human universal found in crafting and creating connections through creative practices really resonated with me.

Why do you work with the compression technique and choose to continuously create a similar sweatshirt shape?

Yasia: The workshop participants make a plain canvas, like a blanket from the clothes they bring. After that, I come in and I compress the canvas for the wrinkled texture.

There are several reasons why I’m making this. First of all, some textile materials with different textures are hard to combine, for example sweatshirt-jersey with chiffon. They have different technical make ups and tensions. When I founded my brand ‘XOMEHKO’, I thoroughly researched how to combine different materials and came up with the compression technique that allows us to combine textiles with very different textures and thicknesses. So, there is no limitation of textiles that people can bring to the workshop.

Why a sweatshirt shape? As the workshops are a sort of ‘new factory’, I wanted to create a new, universal factory object – something very simple. It’s something almost everyone wears and feels connected to.

The final items are then showcased as part of the museum exhibition. It’s a non-commercial project, the items are not sold, it’s not my work, they are in common belonging.

Lara: Have you had experiences where participants of the workshop were disappointed that there wasn't anything that they could take home? Is it hard to move beyond that transactional mindset?

Yasia: Yes. One woman, she was a designer, who joined the workshop in Poland asked, “When can I come and take it home?” I explained that the clothes she brought, and her time was a sort of donation to the project, and she got very angry and even wrote letters to the museum to complain.

The second was a woman in Lviv. She came to the workshop and was looking at the items that were finished and she said, “Oh, I don't wear that.” So I explained the project and the whole process and she asked, “So, I can’t take this item with me?” I said, “No”, and she just turned around and went.

But that was the only two. Everyone else is super friendly, open-minded and excited about the collaboration.

"I think that for fashion right now, it's a very good time to bring crafts back again. For craft people to flourish and rise again, that’s very cool."

Lara: I also studied fashion design and used to work in design and production. Now, I mainly just make clothes for myself and whenever I wear something I made, the first thing my friends tell me is: “You should sell this!” I can imagine that people probably have a similar reaction when they see the outcomes of ‘The practice of social interaction’. How do you resist this drive to commodify your practice or how do you find a balance between a commercial and non-commercial, community-based practice?

Yasia: ‘The practice of social interaction’ is not the only thing I am working on. I'm still reworking broken textiles with this compression practice into some pieces. I am not actively selling them right now but maybe I will. But I need to find a way to communicate the difference to ‘The practice of social interaction’, to clearly communicate that the pieces that I sell are solely made by me. The items created through ‘The practice of social interaction’ are definitely not for sale. I'm glad that I have this opportunity to not make everything for sale.

Lara: When I told you that we wanted to work with a local photographer for this shoot for OC.M you sent me a long list of suggestions. Dmytro Prutkin, who is also a friend of yours, visited you in your studio in Kyiv to photograph you for this interview. It seems like you have a supportive, tight-knit and active creative community in Kyiv despite the war…

Yasia: Everything holds onto community. We are a very good example of community emerging in the context of emergency. I think that stress through missile attacks at night and lots of stress factors all round makes people gather more. Previously the creative community was more dispersed: people were traveling abroad, they were not concentrated in Ukrainian.

We have little to no governmental support for culture because of the war. People are really trying to gather their friends and resources together and put on self-funded stuff and it’s fantastic. People try to share as much as they can. Lots of artists are opening their own galleries in their studios and they're putting on exhibitions every month, so creative productivity is mega high. People are working 24/7 because they need to regenerate and work through that PTSD inflicted by the war and to transform it into some kind of creative outlet.

What we can witness right now is the rising of a strong, new artistic community in Ukraine that is super thirsty for everything: for participatory evenings, for exhibitions, for self-published books. It’s hard to keep up with everything happening in Kyiv; it’s very active.

I think that it's very important for people during the war to realise themselves as the creators of a new Ukrainian now. It’s not only about their individual careers but also about something common. I am really proud of how this community of artists is growing.

Lara: You attended our last OC.M assembly for a fashion commons at the Global Fashioning Assembly 2024, where we explored how to reclaim community practices in fashion and how to transition to a fashion commons. In the deliberation part of the assembly participants discussed practical strategies to realise fashion and textile initiatives that centre care and community. This question of strategies for trans-formation constantly comes up at our events. Can you offer any practical advice for realising participatory and community-based fashion and textile practices? How can we realise these ideas of alternatives?

Yasia: Yes, I think the most important advice is to improve communication, to find a language in which you can talk to everyone in your community. Not everyone is an insider to your field and understands what you do, so clear communication, a simple, inspiring language is vital.

"Every time I listen to lectures about sustainable fashion or similar, I realise that it’s not about system change. The conversation is very surface level, it’s about painting the system green but not tackling the structures. In the end, the fashion industry always faces this question of profit. “The system must work for profit!”, is the main manifesto of the fashion industry."

Lara: What is your vision for a fashion and clothing system beyond the Fashion industry?

Yasia: ‘The practice of social interaction’ is not about positively changing the industry, it’s a soft questioning of the fashion system. It's playful; it’s about leisure for people. When you prioritise a process over results you make the industry uncomfortable.

Every time I listen to lectures about sustainable fashion or similar, I realise that it’s not about system change. The conversation is very surface level, it’s about painting the system green but not tackling the structures. In the end, the fashion industry always faces this question of profit. “The system must work for profit!”, is the main manifesto of the fashion industry.

I think that for fashion right now, it's a very good time to bring crafts back again. For craft people to flourish and rise again, that’s very cool. It’s a good marker for how fashion moves.

The most important thing that fashion and crafts practices should bring about, is that people no longer identify as consumers. That’s true sustainability. But fashion [industry] is not interested in that. They can sell upcycling, upcycling, upcycling… but the industry is not interested in people who are not into the [industrial] system, who arrange themselves outside of the materialistic world.

As someone who used to and is still selling clothes, it is not comfortable to give up on commercial practices. But it is a cool moment, to let this process deconstruct you - so to say: OK, yes, I will lose some money, I will lose some influence maybe. But why not? Why can’t I let myself be in this stage?

"The first thing I wish for, for myself and my community, is the end of the war. That’s the most important thing. And to not let this happen to other countries, to keep all communities alive."

Lara: Lastly, I want to ask you, what sort of support do you need and what do you wish for yourself and your community?

Yasia: That’s a good question. The first thing I wish for, for myself and my community, is the end of the war. That’s the most important thing. And to not let this happen to other countries, to keep all communities alive.

The second thing I wish for is the unexpected, for people to question themselves, push the boundaries of the self and express themselves – for me as well. It’s very hard to deconstruct our social image. Even when we were taking these photos I tried to pose like a serious artist, and I realised that it’s hard to take off this mask. I want to be more flexible with the idea of who I am.

This also applies to who we are in the context of the war: we should not just perceive ourselves and portray ourselves as victims of deconstruction but also as a part of recreation.

Yasia Khomenko’s Instagram

Website: xomehko.com/

Dmytro Prutkin’s Instagram